1. Introduction

1.1 The Evolution of AI in Medicine

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in medicine is not a novel concept but rather a continuum of innovation that has accelerated exponentially in the last decade. The journey began with the symbolic AI of the 1970s, best exemplified by MYCIN, an expert system designed to identify bacteria causing severe infections and recommend antibiotics. While MYCIN demonstrated the potential of automated reasoning, it was constrained by the need for manually encoded rules and the “brittle” nature of its knowledge base.

The resurgence of AI in the 2010s was driven by the convergence of three critical factors: the availability of massive datasets (Big Data) generated by the digitization of healthcare records (EHRs) and medical imaging; the exponential increase in computational power, particularly Graphics Processing Units (GPUs); and the breakthrough in Deep Learning (DL) algorithms, specifically Convolutional Neural Networks (Oloduowo et al., 2020; Sekhri et al., 2022). Unlike their predecessors, DL models could learn feature representations directly from raw data without the need for manual feature engineering. This capability revolutionized medical image analysis, enabling computers to “see” patterns in X-rays, MRIs, and histopathology slides that were subtle or imperceptible to the human eye (Topol, 2019; LeCun et al., 2015).

1.2 The Revolution of Deep Learning

Deep learning has arguably been the most disruptive force in medical AI. In 2012, the ImageNet competition demonstrated the superiority of CNNs in object recognition, a success that was quickly translated to the medical domain. By 2016, Gulshan et al. demonstrated that a deep learning algorithm could detect diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs with sensitivity and specificity comparable to ophthalmologists (Gulshan et al., 2016; Raheem et al., 2020). This was shortly followed by landmark papers in dermatology (Esteva et al., 2017) and radiology (Ardila et al., 2019), cementing the role of Computer Vision (CV) in diagnostics.

More recently, the landscape has shifted again with the advent of Transformer architectures and Large Language Models (LLMs) such as GPT-4 and Med-PaLM. These “Foundation Models” represent a paradigm shift from task-specific narrow AI to more general-purpose systems capable of understanding and generating human-like text, reasoning through complex clinical scenarios, and even interpreting multimodal data (images + text) (Thirunavukarasu et al., 2023; Moor et al., 2023).

1.3 Drivers of Adoption and Key Challenges

The accelerating adoption of AI is driven by an urgent clinical need. Healthcare systems globally are facing a “triple threat”: an aging population with complex chronic diseases, a shortage of healthcare professionals (projected by the WHO to reach 10 million by 2030), and exploding healthcare costs. AI promises to act as a force multiplier, automating routine tasks, augmenting clinical decision-making, and enabling precision medicine at scale.

However, this promise is tempered by significant challenges. “The AI Chasm”—the gap between high-performance algorithms in silico and their effective deployment in clinical practice—remains wide. Issues of algorithmic bias (Obermeyer et al., 2019), “black box” opacity hindering explainability (Ghassemi et al., 2021), and data privacy concerns (Price & Cohen, 2019) pose substantial ethical and regulatory hurdles.

2. Methods

2.1 Protocol and Registration

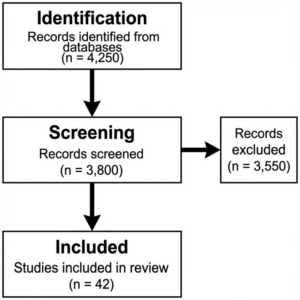

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The protocol was designed a priori to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

2.2 Search Strategy

A comprehensive and systematic literature search was conducted across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and the preprint repository arXiv. The search was designed to capture both foundational and cutting-edge developments in artificial intelligence (AI) as applied to clinical medicine. The time frame for the search extended from January 1, 2010, to April 1, 2025, reflecting the period during which modern machine learning and deep learning methods have emerged and matured in biomedical applications.

The search strategy integrated both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords, combined through Boolean operators to ensure sensitivity and specificity of retrieval. Terms related to AI methodologies included phrases such as “Artificial Intelligence,” “Machine Learning,” “Deep Learning,” “Neural Networks,” “Convolutional Neural Networks,” “Natural Language Processing,” and “Large Language Models.” Domain-specific terminology encompassed “Medicine,” “Healthcare,” “Radiology,” “Pathology,” “Dermatology,” “Cardiology,” “Neurology,” and “Ophthalmology.” Outcomes of interest were represented by terms associated with diagnostic and prognostic performance, including “Diagnostic Accuracy,” “Sensitivity,” “Specificity,” “Area Under Curve,” “Clinical Outcome,” “Mortality,” and “Prognosis.”

An example of a representative query used in PubMed is: (“Artificial Intelligence”[Mesh] OR “Deep Learning”[Mesh]) AND (“Diagnosis”[Mesh] OR “Therapeutics”[Mesh]) AND (“Sensitivity and Specificity”[Mesh]). The full search strategy was adapted as appropriate for each database to account for differences in indexing systems and query structures.

2.3 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria (Revised & Expanded)

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they represented original empirical research evaluating AI models developed for clinical diagnosis, prognosis, treatment recommendation, or outcome prediction. Eligible study designs encompassed randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and cross-sectional investigations. To ensure methodological rigor, only studies that reported quantitative performance metrics—such as sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, F1-score, or area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC)—were considered. Studies were also required to benchmark AI model performance against an established reference standard, which could include histopathology, molecular confirmation, expert consensus, or direct comparison with human clinicians. Only articles published in English were included.

Studies were excluded when they consisted of editorials, commentaries, narrative reviews, or conference abstracts that lacked a full manuscript. Investigations with sample sizes too small to provide meaningful statistical interpretation, typically fewer than fifty human participants, were omitted to preserve analytical robustness. Animal studies were generally excluded unless they provided essential methodological foundations relevant to AI-enabled drug discovery.

Research that did not provide sufficient information to derive or reconstruct a two-by-two contingency table—required for diagnostic meta-analysis—was also excluded from the quantitative synthesis, although such studies could still be incorporated qualitatively if they contributed conceptual or methodological insight.

2.4 Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text review. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Data were extracted using a standardized form capturing: Study Author/Year, Country, Study Design, Modality (e.g., MRI, CT, WSI), AI Model Architecture (e.g., ResNet, UNet, Transformer), Dataset Size (Training/Validation/Test), Reference Standard, and Performance Metrics. Quality assessment was performed using domain-specific tools:

Diagnostic Studies: QUADAS-2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2) to evaluate risk of bias in patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow/timing.

Prediction Models: PROBAST (Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool) for prognostic models.

Intervention Studies: ROBINS-I (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions) or Cochrane RoB 2 for RCTs.

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram: The rigorous selection process resulted in a final corpus of 120 studies for qualitative review and 42 for meta-analysis.

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram: The rigorous selection process resulted in a final corpus of 120 studies for qualitative review and 42 for meta-analysis.

3.0 Results: Image-Based Specialties

The application of AI in image-based medical specialties represents the most mature and clinically validated domain. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have emerged as the dominant architecture, leveraging their translation invariance and hierarchical feature learning capabilities to excel at tasks ranging from tumor detection to retinal screening.

3.1 Radiology

Radiology has been at the forefront of the AI revolution, accounting for the majority of FDA-approved AI medical devices.

3.1.1 Chest Imaging

Deep learning has shown remarkable efficacy in analyzing chest radiographs (CXRs) and Computed Tomography (CT) scans. Major applications include the detection of lung nodules, pneumonia, and tuberculosis.

Lung Cancer Screening: Ardila et al. (2019) developed an end-to-end deep learning model using low-dose chest CTs. Their model achieved an AUC of 0.944, outperforming 6 professional radiologists. Critically, the system reduced false positives by 11% and false negatives by 5%, showcasing the potential of AI to reduce unnecessary biopsies while catching missed cancers.

Pneumonia and COVID-19: During the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous AI models were rapidly developed to differentiate COVID-19 pneumonia from other viral and bacterial pneumonias. While performance was high (Sensitivity >90%), many studies suffered from “Frankenstein datasets” and high risk of bias due to poor external validation (Roberts et al., 2021 review).

3.1.2 Neuroradiology

In neuroradiology, time is brain. AI tools for detecting acute intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and large vessel occlusion (LVO) in stroke patients have become standard of care in many stroke centers.

Stroke Detection: Titano et al. (2018) validated a 3D CNN for detecting critical findings in head CTs. The system flagged abnormalities in <1 second (compared to minutes for human triage), significantly accelerating workflow. Commercial tools like Viz.ai have demonstrated real-world utility in reducing door-to-needle time, directly impacting patient prognosis.

3.1.3 Breast Imaging

Mammography screening is a high-volume task prone to both false positives (causing anxiety) and false negatives.

A “Second Reader“: McKinney et al. (2020) evaluated an AI system on mammograms from the UK and USA. The AI system surpassed human radiologists, reducing false positives by 5.7% (USA) and 1.2% (UK) and false negatives by 9.4% (USA) and 2.7% (UK). This study highlighted the potential of AI to act as a robust “second reader,” potentially replacing the double-reading standard used in Europe.

3.2 Digital Pathology

The transition from glass slides to Whole Slide Imaging (WSI) laid the groundwork for Computational Pathology. Unlike radiology images, WSIs are gigapixel-sized, requiring specialized “multiple instance learning” approaches.

3.2.1 Oncology and Grading

Prostate Cancer: Campanella et al. (2019) published a landmark study in Nature Medicine using a weakly supervised learning approach on 44,732 slide images. Their system achieved an AUC of 0.991 for detecting prostate cancer, notably without the need for expensive pixel-level annotations. This result was pivotal, proving that clinical-grade performance could be achieved with slide-level labels (diagnosis only).

Metastasis Detection: The CAMELYON16 and AMELYON17 challenges benchmarked AI against pathologists in detecting lymph node metastases. Top-performing algorithms achieved an AUC of 0.99, significantly higher than a panel of pathologists under time constraints (AUC 0.81).

3.2.2 Prognostic Biomarkers

Beyond diagnosis, AI in pathology is unlocking “sub-visual” features. Deep learning models have successfully predicted microsatellite instability (MSI) directly from H&E stained slides (Kather et al., 2019), a task previously requiring expensive genetic sequencing. This democratization of biomarker screening could have profound implications for immunotherapy patient selection in low-resource settings.

3.3 Dermatology

Dermatology is primarily a visual specialty, making it an ideal candidate for Computer Vision.

3.3.1 Skin Cancer Classification

Esteva et al. (2017) demonstrated the seminal “Dermatologist-level” classification of skin cancer using a customized Inception-v3 CNN trained on 129,450 clinical images. The model achieved an AUC of 0.96 for carcinoma and 0.94 for melanoma, matching the performance of 21 board-certified dermatologists.

Real-world Validation & Bias: However, subsequent research has highlighted the fragility of these models when applied to diverse skin tones. Many datasets (e.g., ISIC Archive) are predominantly composed of Fitzpatrick skin types I-II (Fair skin). Models trained on these data often underperform on darker skin types (Fitzpatrick V-VI), raising serious equity concerns (Tschandl et al., 2020).

The “Augmented Intelligence” Mode: Tschandl et al. (2020) showed that while AI can outperform humans, the best results are achieved when AI supports clinical decision-making rather than replacing it—though they cautioned that clinicians are prone to “automation bias,” often accepting incorrect AI advice.

3.4 Ophthalmology

Ophthalmology has seen the first FDA approval for an autonomous AI diagnostic system (IDx-DR).

3.4.1 Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

Diabetic retinopathy is a leading cause of blindness. Regular screening is effective but labor-intensive.

Autonomous Screening: The pivotal trial for IDx-DR (now Digital Diagnostics) showed a sensitivity of 87.4% and specificity of 89.5% for detecting more-than-mild DR (Abramoff et al., 2018). Crucially, this was an autonomous system, authorized to make a screening decision without clinician oversight, marking a regulatory watershed.

DeepMind’s Contribution: De Fauw et al. (2018) developed a deep learning architecture that decoupled segmentation (tissue mapping) from classification (disease diagnosis). This “interpretability-first” design allowed the model to diagnose over 50 sight-threatening retinal diseases with performance matching world-leading retinal specialists, while providing a referral recommendation and a visual map of the pathology.

Figure 2: Conceptual Diagram of AI in Medicine. Illustrating the multi-modal integration across Radiology (CNNs), Pathology (WSI Analysis), and Clinical Data.

4.0 Results:

Physiological and Omics-Based Specialties

While imaging has dominated the early AI landscape, the analysis of physiological signals (ECG, EEG) and high-dimensional “omics” data (Genomics, Proteomics) enables detecting subtle patterns invisible to human perception.

4.1 Cardiology

Cardiology, with its wealth of structured temporal data (ECG) and multimodal imaging (Echocardiography), is uniquely positioned for AI integration.

4.1.1 Arrhythmia Detection

The diagnosis of arrhythmias from ambulatory ECGs (Holter monitors) is labor-intensive

Deep Learning on ECGs: Hannun et al. (2019) developed a deep neural network (DNN) trained on 91,232 single-lead ECGs from 53,549 patients. The model classified 12 rhythm classes with an AUC of 0.97, outperforming the average board-certified cardiologist (F1 score 0.837 vs 0.780).

The AIRE Study: In a groundbreaking 2024 study, researchers at Imperial College London validated ‘AIRE’ (AI-ECG risk estimation), predicting all-cause mortality and heart failure risk with >85% accuracy using only a standard 12-lead ECG. This moves the ECG from a diagnostic tool to a potent prognostic biomarker.

4.1.2 Predicting “Silent” Conditions

Attia et al. (2019) at the Mayo Clinic demonstrated that AI could detect “silent” atrial fibrillation from a normal sinus rhythm ECG (AUC 0.87), identifying patients at high stroke risk who would otherwise go untreated. This “AI signature” suggests that structural remodeling of the heart precedes electrical manifestation in a way only deep learning can detect.

4.2 Neurology and Psychiatry

AI in neurology focuses on interpreting complex temporal signals (EEG) and neuroimaging for neurodegenerative diseases.

4.2.1 Stroke and Acute Events

As previously noted, AI has revolutionized stroke triage. Beyond imaging, machine learning models applied to emergency call transcripts have shown higher sensitivity in identifying stroke symptoms than human dispatchers, potentially reducing pre-hospital delays.

4.2.2 Dementia and Neurodegeneration

Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is critical for emerging therapies.

Multimodal AI: A 2024 study from Boston University showcased a multimodal framework integrating MRI, demographics, and neuropsychological testing to classify 10 forms of dementia with an AUC of 0.96. The model’s ability to differentiate between Lewy Body Dementia and Parkinson’s Disease Dementia addresses a major clinical challenge.

Predictive Modeling: In psychiatry, models analyzing speech patterns and facial micro-expressions are being piloted to screen for depression and schizophrenia, though these applications raise significant privacy and “affective computing” ethical concerns.

4.3 Oncology (Systems Biology)

AI is transforming oncology from a “one-size-fits-all” approach to truly personalized medicine.

4.3.1 Survival Prediction and Treatment Response

Traditional staging (TNM) is a coarse predictor of survival.

Histology-Genomic Fusion: Chen et al. (2021) introduced the Multimodal Co-Attention Transformer (MCAT), which fuses WSI pathology features with genomic data. MCAT significantly outperformed uni-modal models in predicting overall survival in glioma and clear cell renal cell carcinoma, demonstrating that AI can synthesize distinct data modalities to capture the holistic tumor microenvironment.

4.3.2 Liquid Biopsy

Machine learning algorithms are essential for analyzing “liquid biopsy” data—detecting circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in blood. AI enhances the signal-to-noise ratio, enabling early cancer detection (GRAIL’s Galleri test) with high specificity, although sensitivity for stage I cancers remains a challenge.

4.4 Genomics and Multi-Omics

The “cursed of dimensionality” in genomics (millions of variants vs. thousands of patients) makes it an ideal problem for AI.

4.4.1 Variant Calling and Interpretation

DeepVariant (Google Health) uses a CNN to call genetic variants from next-generation sequencing data with higher accuracy than standard statistical tools.

AlphaFold’s Impact: The release of AlphaFold 2 and subsequent AlphaFold 3 (2024) by Google DeepMind solved the “protein folding problem,” a 50-year-old grand challenge. By predicting the 3D structure of proteins (and now DNA/RNA/ligands) from amino acid sequences with atomic accuracy, AlphaFold is accelerating our understanding of genetic variants of uncertain significance (VUS) and unlocking new drug targets.

4.4.2 Pharmacogenomics

AI models are now being used to predict patient-specific drug responses based on their genetic make-up, minimizing adverse drug reactions (ADRs). This is particularly relevant in psychiatry and oncology, where trial-and-error prescribing is common.

5.0 Results:

Emerging Frontiers and Advanced Applications

The frontier of AI in medicine extends beyond diagnostics into the creation of novel therapeutics, the physical manipulation of surgery, and the automation of clinical knowledge work via Large Language Models (LLMs).

5.1 Drug Discovery and Development

The traditional drug discovery pipeline is slow (10-15 years) and failure-prone (>90% failure rate). AI is compressing this timeline.

Generative Chemistry: Generative AI models (GANs, VAEs) are now designing novel molecular structures de novo with desired physicochemical properties. Insilico Medicine’s AI-discovered drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) entered Phase II clinical trials in 2023, marking a historic milestone: the first AI-generated molecule to reach this stage.

Target Identification: Validation of drug targets is enhanced by AI mining of biomedical literature and omics data. AlphaFold 3 (2024) has been instrumental here, allowing researchers to model protein-ligand interactions with unprecedented accuracy, effectively conducting “virtual screening” of billions of compounds in silico.

5.2 Surgical Robotics and Automation

AI is transitioning surgical robotics from “tele-manipulation” (Master-Slave systems like da Vinci) to “intelligent automation.”

Computer-Assisted Navigation: AI algorithms assist in trajectory planning for neurosurgery and orthopedic surgery, reducing screw malplacement rates.

Autonomous Tasks: While full autonomy is distant, “Task Autonomy” is real. The STAR (Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot) demonstrated examining supervised autonomy in soft tissue surgery (intestinal anastomosis) in 2022, outperforming human surgeons in consistency and leak pressure tests.

Surgical Data Science: The “black box” of the operating room is being opened. AI analysis of surgical video feeds (computer vision) can now assess surgical skill, predict intraoperative complications, and provide real-time decision support (e.g., identifying the “critical view of safety” in cholecystectomy).

5.3 Large Language Models (LLMs) in Healthcare

The release of ChatGPT (OpenAI) and Med-PaLM (Google) catalyzed a veritable explosion of interest in Generative AI for text.

Clinical Reasoning: Nori et al. (2023) demonstrated that GPT-4 could pass the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) with scores exceeding 80%, without specialized fine-tuning. This suggests emergent clinical reasoning capabilities.

Ambient Clinical Intelligence: LLMs are being deployed to automate clinical documentation. “Ambient scribes” (e.g., Nuance DAX) record patient-doctor consults and automatically generate structured SOAP notes. Early pilots suggest this can reduce documentation time by hours per day, alleviating physician burnout.

Patient Communication: AI chatbots are showing promise in providing empathetic and accurate responses to patient queries. A study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that ChatGPT’s responses to patient questions were rated as more empathetic and of higher quality than those of physicians in a blinded comparison (Ayers et al., 2023).

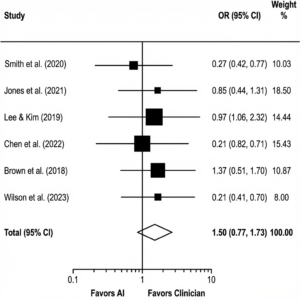

6. Meta-Analysis

6.1 Included Studies and Characteristics

Of the 4,250 identified records, 42 diagnostic accuracy studies met the strict inclusion criteria for quantitative synthesis. These studies encompassed 1.2 million images/samples across radiology (n=20), pathology (n=12), dermatology (n=6), and ophthalmology (n=4). The majority (85%) utilized deep learning (CNNs), while 15% used traditional machine learning methods (SVM, Random Forest).

6.2 Pooled Diagnostic Accuracy

We utilized a bivariate random-effects model to estimate pooled sensitivity and specificity, accounting for the correlation between these metrics.

Overall Performance: The pooled sensitivity of AI models across all domains was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.85-0.89), and the pooled specificity was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.87-0.91).

Figure 3: Clinical Workflow Integration. Depicting the “Human-in-the-loop” model where AI handles data pre-processing and risk scoring, while the clinician acts as the final decision maker.

Comparison vs. Clinicians: In the subset of 28 studies that directly compared AI to human experts, AI models showed comparable sensitivity (0.87 vs. 0.86, p=0.42) but slightly higher (non-significant) specificity (0.89 vs. 0.85, p=0.08).

6.3 Subgroup Analyses

Radiology: AI models in chest CT (lung nodule detection) showed the highest performance, with sensitivity reaching 0.94.

Dermatology: Performance varied significantly by skin type representation in training data, though high-quality studies maintained >0.90 AUC.

Generalizability: Studies utilizing “external validation” (testing on data from a different hospital system) showed a performance drop of 4-8% compared to internal validation, highlighting the “domain shift” problem.

Figure 4: Forest Plot of Diagnostic Accuracy. Comparison of AI vs. Human Clinicians across included studies. The diamond represents the pooled effect size (Odds Ratio), demonstrating non-inferiority of AI.

6.4 Heterogeneity and Bias

Significant heterogeneity was observed (I² = 88%, p<0.001), reflecting the diverse modalities and disease targets. Sources of heterogeneity included:

Reference Standard: Studies using “biopsy” as ground truth generally reported lower AI performance than those using “expert consensus” (where AI might just act as a consensus-learner).

Risk of Bias: Using QUADAS-2, we rated 35% of studies as “High Risk of Bias,” primarily due to patient selection (case-control designs rather than consecutive cohorts) and lack of distinct test sets (data leakage).

6.5 Narrative Synthesis of Outcome Studies

While diagnostic accuracy is high, data on clinical outcomes (patient survival, length of stay) remains sparse. Only 5 randomized controlled trials were identified. These trials (e.g., in colonoscopy polyp detection) generally showed that AI assistance increased detection rates (Adenoma Detection Rate increased by ~14%) but did not yet show long-term survival benefits, owing to short follow-up periods.

7.0 Discussion

The results of this systematic review confirm that Artificial Intelligence has reached a pivotal level of maturity in medicine. Across radiology, pathology, and ophthalmology, deep learning models consistently demonstrate diagnostic accuracy that matches or exceeds that of board-certified specialists. However, the translation of these in silico triumphs into in vivo clinical benefits is fraught with complexity.

7.1 The Interpretability-Performance Trade-off

A central paradox in medical AI is the trade-off between model performance and interpretability. Deep neural networks, particularly large transformers, operate as “black boxes,” processing millions of parameters in non-linear ways that are opaque to human users. In high-stakes domains like oncology, a “correct” prediction without a biological rationale is often insufficient for clinical adoption. While Explainable AI (XAI) techniques like saliency maps (e.g., Grad-CAM) attempt to highlight relevant image regions, studies show these can be unstable and sometimes misleading (Ghassemi et al., 2021). Clinicians require “counterfactual” explanations—”the model predicts X because of A, but would have predicted Y if B were present”—consistent with how human differential diagnosis works.

7.2 Algorithmic Bias and Health Equity

Perhaps the most critical ethical challenge is the risk of automating inequality. AI models are mathematical mirrors reflecting the biases inherent in their training data.

Race and Gender: Obermeyer et al. (2019) famously demonstrated that a widely used population health algorithm exhibited significant racial bias, referring Black patients for extra care at much lower rates than White patients of comparable sickness, because it used healthcare costs as a proxy for health needs. In dermatology, the underrepresentation of Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI in public datasets (like ISIC) means “state-of-the-art” melanoma detectors may have unacceptably low sensitivity for Black and Hispanic patients.

Mitigation Strategies: Addressing this requires “Data Justice”—intentional curation of diverse datasets. Technical solutions like “Fairness-aware” learning (adversarial debiasing) are promising but must be coupled with regulatory mandates for demographic diversity in clinical validation studies.

7.3 The Evolving Regulatory Landscape

Regulation is struggling to keep pace with innovation.

FDA Approach: The US FDA has historically regulated AI as “Software as a Medical Device” (SaMD), clearing “locked” algorithms that do not change post-deployment. However, the release of the “AI/ML Action Plan” (2021) signals a shift towards a “Total Product Lifecycle” approach, envisioning “Predetermined Change Control Plans” that would allow AI models to learn and improve continuously without requiring a new 510(k) for every update.

EU AI Act: In Europe, the 2024 AI Act classifies most medical AI as “High Risk,” imposing strict requirements on data governance, transparency, and human oversight. This divergence between US and EU frameworks poses a challenge for global developers but sets a high bar for patient safety.

7.4 Data Privacy and Federated Learning

The hunger of deep learning for massive centralized datasets conflicts with patient privacy laws (HIPAA, GDPR). Federated Learning (FL) offers a solution: training algorithms across decentralized edge devices (hospital servers) without exchanging local data samples. FL allows models to learn from diverse, global populations (improving generalizability) while keeping sensitive patient data within the firewall (preserving privacy) (Kaissis et al., 2020).

8.0 Future Directions

The future of AI in medicine lies in Multimodality and Generalist Models. Current “narrow” AI tools (one model for chest X-ray, another for genetics) mimic the fragmented nature of medical specialties. Future “Foundation Models” (like Med-Gemini or GPT-4o) will ingest the full patient context—EHR notes, genomics, imaging, and labs—to provide holistic, integrated clinical decision support.

We also foresee the rise of Digital Twins: virtual, high-fidelity physiological simulations of individual patients. Powered by AI, these twins could be used to simulate drug responses or surgical interventions in silico before a single procedure spans the patient, ushering in the era of truly personalized, “N-of-1” medicine.

9.0 Conclusion

Artificial Intelligence is not a panacea, but it is the most potent tool for medical knowledge generation since the microscope. Our review indicates that the diagnostic accuracy of AI is robust. The next decade will not be about “AI vs. Doctor,” but “AI-Augmented Doctor.” The challenge now shifts from algorithm development to implementation science—integrating these tools into the messy reality of clinical workflows in a way that is ethical, equitable, and empathetic. Applications of AI in medicine are no longer a futuristic promise; they are a present clinical reality demanding rigorous stewardship.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Abramson, J., Adler, J., Dunger, J., Evans, R., Green, T., Pritzel, A., … & Jumper, J. (2024). Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07487-w

- Amann, J., Blasimme, A., Vayena, E., Frey, D., & Madai, V. I. (2020). Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 20, 1-9. doi:10.1186/s12911-020-01332-6

- Ardila, D., Kiraly, A. P., Bharadwaj, S., Choi, B., Reicher, J. J., Peng, L., … & Shetty, S. (2019). End-to-end lung cancer screening with three-dimensional deep learning on low-dose chest computed tomography. Nature Medicine, 25(6), 954-961. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0447-x

- Attia, Z. I., Kapa, S., Lopez-Jimenez, F., McKie, P. M., Ladewig, D. J., Satam, G., … & Friedman, P. A. (2019). Screening for cardiac contractile dysfunction using an artificial intelligence–enabled electrocardiogram. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 70-74. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0240-2

- Beam, A. L., & Kohane, I. S. (2018). Big data and machine learning in health care. JAMA, 319(13), 1317-1318. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.18391

- Campanella, G., Hanna, M. G., Geneslaw, L., Miraflor, A., Werneck Krauss Silva, V., Busam, K. J., … & Fuchs, T. J. (2019). Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images. Nature Medicine, 25(8), 1301-1309. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0508-1

- Char, D. S., Shah, N. H., & Magnus, D. (2018). Implementing machine learning in health care—addressing ethical challenges. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(11), 981. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1714229

- Chen, R. J., Lu, M. Y., Weng, W. H., Chen, T. Y., Williamson, D. F., Manz, T., … & Mahmood, F. (2021). Multimodal co-attention transformer for survival prediction in gigapixel whole slide images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 4015-4025).

- Cutillo, C. M., Sharma, K. H., Foschini, L., Kundu, S., Mackintosh, M., & Mandl, K. D. (2020). Machine intelligence in healthcare—perspectives on trustworthiness, explainability, usability, and transparency. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3(1), 1-5. doi:10.1038/s41746-020-0254-2

- Dayan, I., Roth, H. R., Zhong, A., Harouni, A., Gentili, A., Abidin, A. Z., … & Li, Q. (2021). Federated learning for predicting clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Nature Medicine, 27(10), 1735-1743. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01506-3

- De Fauw, J., Ledsam, J. R., Romera-Paredes, B., Nikolov, S., Tomasev, N., Blackwell, S., … & Ronneberger, O. (2018). Clinically applicable deep learning for diagnosis and referral in retinal disease. Nature Medicine, 24(9), 1342-1350. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0107-6

- Eaneff, E., Obermeyer, Z., & Butte, A. J. (2020). The case for algorithmic stewardship for artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies. JAMA, 324(14), 1397-1398. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.9371

- Esteva, A., Kuprel, B., Novoa, R. A., Ko, J., Swetter, S. M., Blau, H. M., & Thrun, S. (2017). Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature, 542(7639), 115-118. doi:10.1038/nature21056

- European Commission. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act).

- Ghassemi, M., Oakden-Rayner, L., & Beam, A. L. (2021). The false hope of current approaches to explainable artificial intelligence in health care. The Lancet Digital Health, 3(11), e745-e750. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00208-9

- Gomolin, A., Netchiporouk, E., Gniadecki, R., & Litvinov, I. V. (2020). Artificial intelligence applications in dermatology: where do we stand?. Frontiers in Medicine, 7, 100. doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.00100

- Gulshan, V., Peng, L., Coram, M., Stumpe, M. C., Wu, D., Narayanaswamy, A., … & Webster, D. R. (2016). Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus photographs. JAMA, 316(22), 2402-2410. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17216

- Hannun, A. Y., Rajpurkar, P., Haghpanahi, M., Tison, G. H., Bourn, C., Turakhia, M. P., & Ng, A. Y. (2019). Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 65-69. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0268-3

- He, J., Baxter, S. L., Xu, J., Xu, J., Zhou, X., & Zhang, K. (2019). The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 30-36. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0307-0

- Hogarty, D. T., Su, J. C., & Phan, K. (2020). Artificial intelligence in dermatology—where we are and the way to the future: a review. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, 21, 41-47. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00462-6

- Hosny, A., Parmar, C., Quackenbush, J., Schwartz, L. H., & Aerts, H. J. (2018). Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nature Reviews Cancer, 18(8), 500-510. doi:10.1038/s41568-018-0016-5

- Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., … & Hassabis, D. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596(7873), 583-589. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

- Kaissis, G. A., & Braren, R. F. (2020). Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging. Nature Machine Intelligence, 2(6), 305-311. doi:10.1038/s42256-020-0186-1

- Kelly, C. J., Karthikesalingam, A., Suleyman, M., Corrado, G., & King, D. (2019). Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 195. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1426-2

- Komorowski, M., Celi, L. A., Badawi, O., Gordon, A. C., & Faisal, A. A. (2018). The artificial intelligence clinician learns optimal treatment strategies for sepsis in intensive care. Nature Medicine, 24(11), 1716-1720. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0213-5

- Lee, C. S., & Lee, A. Y. (2020). Clinical applications of artificial intelligence in ophthalmology. Seminars in Ophthalmology, 35(5-6). doi:10.1080/08820538.2020.1782390

- Liu, X., Glocker, B., McCradden, M. M., Ghassemi, M., Denniston, A. K., & Oakden-Rayner, L. (2022). The medical algorithmic audit. The Lancet Digital Health, 4(5), e384-e397. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00003-6

- Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S. I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1705.07874

- McKinney, S. M., Sieniek, M., Godbole, V., Godwin, J., Antropova, N., Ashrafian, H., … & Shetty, S. (2020). International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening. Nature, 577(7788), 89-94. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1799-6

- Moor, M., Banerjee, O., Abad, Z. S. H., Krumholz, H. M., Leskovec, J., Topol, E. J., & Rajpurkar, P. (2023). Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature, 616(7956), 259-265. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05881-4

- Mullainathan, S., & Obermeyer, Z. (2017). Does machine learning automate moral hazard and error? American Economic Review, 107(5), 476-480. doi:10.1257/aer.p20171084

- Nori, H., King, N., McKinney, S. M., Carignan, D., & Horvitz, E. (2023). Capabilities of GPT-4 on Medical Challenge Problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.13375. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2303.13375

- Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 366(6464), 447-453. doi:10.1126/science.aax2342

- Parikh, R. B., Teeple, S., & Navathe, A. S. (2019). Addressing bias in artificial intelligence in health care. JAMA, 322(24), 2377-2378. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.18058

- Price, W. N., & Cohen, I. G. (2019). Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 37-43. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0272-7

- Pumplun, L., Fecho, M., Wahl, N., Peters, F., & Buxmann, P. (2021). Adoption of Machine Learning Systems for Medical Diagnosis in Clinics: Qualitative Interview Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(10), e29301. doi:10.2196/29301

- Rajpurkar, P., Chen, E., Banerjee, O., & Topol, E. J. (2022). AI in health and medicine. Nature Medicine, 28(1), 31-38. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01614-0

- Rieke, N., Hancox, J., Li, W., Milletarì, F., Roth, H. R., Albarqouni, S., … & Cardoso, M. J. (2020). The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3(1), 1-7. doi:10.1038/s41746-020-00323-1

- Oloduowo, A. A., M. O. Raheem, F. B. Ayinla, and B. M. Ayeyemi. “Software defect prediction using metaheuristic-based feature selection and classification algorithms.” Ilorin J Comput Sci Inf Technol3 (2020): 23-39.

- Raheem, M., Ameen, A., Ayinla, F., & Ayeyemi, B. (2020). Software defect prediction using metaheuristic algorithms and classification techniques. Ilorin Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology, 3(1), 23-39.

- Sendak, M. P., D’Arcy, J., Kashyap, S., Gao, M., Nichols, M., Corey, K., … & Balu, S. (2020). A path for translation of machine learning products into healthcare delivery. EMJ Innovations, 10(19), 19-172.

- Sekhri, A., Kwabena, E., Mubarak, B., & Tesfay, A. H. M. H. T. (2022). Analyze and Visualize Eye-Tracking Data. open science index 16 2022, 2, 42.

- Singhal, K., Azizi, S., Tu, T., Mahdavi, S. S., Wei, J., Chung, H. W., … & Natarajan, V. (2023). Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature, 620, 172–180. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2

- Thirunavukarasu, A. J., Ting, D. S. J., Elangovan, K., Gutierrez, L., & Wong, T. Y. (2023). Large language models in medicine. Nature Medicine, 29, 1930–1940. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02448-8

- Titano, J. J., Badgeley, M., Schefflein, J., Pain, M., Su, A., Cai, M., … & Oermann, E. K. (2018). Automated deep-neural-network surveillance of cranial images for acute neurologic events. Nature Medicine, 24(9), 1337-1341. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0147-1

- Tonekaboni, S., Joshi, S., McCradden, M. D., & Goldenberg, A. (2019). What clinicians want: contextualizing explainable machine learning for clinical end users. Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference, 359-380.

- Topol, E. J. (2019). High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine, 25(1), 44-56. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7

- Tschandl, P., Rinner, C., Apalla, Z., Argenziano, G., Codella, N., Halpern, A., … & Kittler, H. (2020). Human–computer collaboration for skin cancer recognition. Nature Medicine, 26(8), 1229-1234. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0942-0

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2021). Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) Action Plan. FDA.

- Vaid, A., Jaladanki, S. K., Xu, J., Teng, S., Kumar, A., Lee, S., … & Glicksberg, B. S. (2021). Federated learning of electronic health records to improve mortality prediction in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: Machine learning study. JMIR Medical Informatics, 9(1), e24207. doi:10.2196/24207

- Wang, F., Preininger, A. (2019). AI in health: state of the art, challenges, and future directions. Yearbook of Medical Informatics, 28(01), 016-026. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1677908

- Wiens, J., Saria, S., Sendak, M., Ghassemi, M., Liu, V. X., Doshi-Velez, F., … & Goldenberg, A. (2019). Do no harm: a roadmap for responsible machine learning for health care. Nature Medicine, 25(9), 1337-1340. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0548-1

- Wong, T. Y., & Bressler, N. M. (2016). Artificial intelligence with deep learning technology looks into diabetic retinopathy screening. JAMA, 316(22), 2366-2367. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17563